11 Random Forests

This page is a work in progress and minor changes will be made over time.

Random forests are a composite (or ensemble) algorithm built by fitting many simpler component models, decision trees, and then averaging the results of predictions from these trees. Due to in-built variable importance properties, random forests are commonly used in high-dimensional settings when the number of variables in a dataset far exceeds the number of rows. High-dimensional datasets are very common in survival analysis, especially when considering omics, genetic and financial data. It is therefore no surprise that random survival forests, remain a popular and well-performing model in the survival setting.

11.1 Random Forests for Regression

Training of decision trees can include a large number of hyper-parameters and different training steps including ‘growing’ and subsequently ‘pruning’. However, when utilised in random forests, many of these parameters and steps can be safely ignored, hence this section only focuses on the components that primarily influence the resulting random forest. This section will start by discussing decision trees and will then introduce the bagging algorithm used to create random forests.

11.1.1 Decision Trees

Decision trees are a (relatively) simple machine learning model that are comparatively easy to implement in software and are highly interpretable. The decision tree algorithm takes an input, a dataset, selects a variable that is used to partition the data according to some splitting rule into distinct non-overlapping datasets or nodes or leaves, and repeats this step for the resulting partitions, or branches, until some criterion has been reached. The final nodes are referred to as terminal nodes.

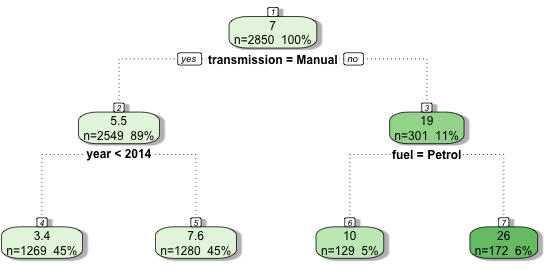

By example, (Figure 11.1) demonstrates a decision tree predicting the price that a car sells for in India (price in thousands of dollars). The dataset includes as variables the registration year, kilometers driven, fuel type (petrol or automatic), seller type (individual or dealer), transmission type (manual or automatic), and number of owners. The decision tree was trained with a maximum depth of 2 (the number of rows excluding the top), and it can be seen that with this restriction only the transmission type, registration year, and fuel type were selected variables. During training, the algorithm identified that the first optimal variable to split the data was transmission type, partitioning the data into manual and automatic cars. Manual cars are further subset by registration year whereas automatic cars are split by fuel type. It can also be seen how the average sale price (top value in each leaf) diverges between leaves as the tree splits – the average sale prices in the final leaves are the terminal node predictions.

The graphic highlights several core features of decision trees:

- They can model non-linear and interaction effects: The hierarchical structure allows for complex interactions between variables with some variables being used to separate all observations (transmission) and others only applied to subsets (year and fuel);

- They are highly interpretable: it is easy to visualise the tree and see how predictions are made;

- They perform variable selection: not all variables were used to train the model.

To understand how random forests work, it is worth looking a bit more into the most important components of decision trees: splitting rules, stopping rules, and terminal node predictions.

Splitting and Stopping Rules

Precisely how the data partitions/splits are derived and which variables are utilised is determined by the splitting rule. The goal in each partition is to find two resulting leaves/nodes that have the greatest difference between them and thus the maximal homogeneity within each leaf, hence with each split, the data in each node should become increasingly similar. The splitting rule provides a way to measure the homogeneity within the resulting nodes. In regression, the most common splitting rule is to select a variable and cut-off (a threshold on the variable at which to separate observations) that minimises the mean squared error in the two potential resulting leaves.

For all decision tree and random forest algorithms going forward, let \(L\) denote some leaf, then let \(L_{xy}, L_x, L_y\) respectively be the set of observations, features, and outcomes in leaf \(L\). Let \(L_{y;i}\) be the \(i\)th outcome in \(L_y\) and finally let \(\bar{y}_L = \frac{1}{|L_y|} \sum^{|L_y|}_{i = 1} L_{y;i}\) be the mean outcome in leaf \(L\).

Let \(j=1,\ldots,p\) be the index of features and let \(c_j\) be a possible cutoff value for feature \(\mathbf{x}_{;j}\). Define \[ \begin{split} L^a_{xy}(j,c_j) := \{(\mathbf{x}_i,y_i)|x_{i;j} \boldsymbol{<} c_j, i = 1,...,n\} \\ L^b_{xy}(j,c_j) := \{(\mathbf{x}_i,y_i)|x_{i;j} \boldsymbol{\geq} c_j, i = 1,...,n\} \end{split} \] as the two leaves containing the set of observations resulting from partitioning variable \(j\) at cutoff \(c_j\). To simplify equations let \(L^a, L^b\) be shorthands for \(L^a(j,c_j)\) and \(L^b(j,c_j)\). Then a split is determined by finding the arguments, \((j^*,c_{j^*}^*)\) that minimise the residual sum of squares across both leaves (James et al. 2013), \[ (j^*, c_{j^*}^*) = \mathop{\mathrm{arg\,min}}_{j, c_j} \sum_{y \in L^a_{y}} (y - \bar{y}_{L^a})^2 + \sum_{y \in L^b_{y}} (y - \bar{y}_{L^b})^2 \tag{11.1}\]

This method is repeated from the first leaf to the last such that observations are included in a given leaf \(L\) if they satisfy all conditions from all previous branches (splits); features may be considered multiple times in the growing process allowing complex interaction effects to be captured.

Leaves are repeatedly split until a stopping rule has been triggered – a criterion that tells the algorithm to stop partitioning data. The stopping rule is usually a condition on the number of observations in each leaf such that leaves will continue to be split until some minimum number of observations has been reached in a leaf. Other conditions may be on the depth of the tree (as in Figure 11.1 which is restricted to a maximum depth of 2), which corresponds to the number of levels of splitting. Stopping rules are often used together, for example by setting a maximum tree depth and determining a minimum number of observations per leaf. Deciding the number of minimum observations and/or the maximum depth can be performed with automated hyper-parameter optimisation.

Terminal Node Predictions

The final major component of decision trees are terminal node predictions. As the name suggests, this is the part of the algorithm that determines how to actually make a prediction for a new observation. A prediction is made by ‘dropping’ the new data ‘down’ the tree according to the optimal splits that were found during training. The resulting prediction is then a simple baseline statistic computed from the training data that fell into the corresponding node. In regression, this is commonly the sample mean of the training outcome data.

Returning to Figure 11.1, say a new data point is {transmission = Manual, fuel = Diesel, year = 2015}, then in the first split the left branch is taken as ‘transmission = Manual’, in the second split the right branch is taken as ‘year’ \(= 2015 \geq 2014\), hence the new data point lands in the second terminal leaf and is predicted to sell for $7,600. The ‘fuel’ variable is ignored as it is only considered for automatic vehicles. As the final predictions are simple statistics based on training data, all potential predictions can be saved in the original trained model and no complex computations are required in the prediction algorithm.

11.1.2 Random Forests

Decision trees often overfit the training data, hence they have high variance, perform poorly on new data, and are not robust to even small changes in the original training data. Moreover, important variables can end up being ignored as only subsets of dominant variables are selected for splitting.

To counter these problems, random forests are designed to improve prediction accuracy and decrease variance. Random forests utilise bootstrap aggregation, or bagging (Leo Breiman 1996), to aggregate many decision trees. Bagging is a relatively simple algorithm, as follows:

- For \(b = 1,...,B\):

- \(D_b \gets \text{ Randomly sample with replacement } \mathcal{D}_{train}\)

- \(\hat{g}_b \gets \text{ Train a decision tree on } D_b\)

- end For

- return \(\{\hat{g}_b\}^B_{b=1}\)

Step 2 is known as bootstrapping, which is the process of sampling a dataset with replacement – which is in contrast to more standard subsampling where data is sampled without replacement. Commonly, the bootstrapped sample size is the same as the original. However, as the same value may be sampled multiple times, on average the resulting data only contains around 63.2% unique observations (Efron and Tibshirani 1997). Randomness is further injected to decorrelate the trees by randomly subsetting the candidates of features to consider at each split of a tree. Therefore, every split of every tree may consider a different subset of variables. This process is repeated for \(B\) trees, with the final output being a collection of trained decision trees.

Prediction from a random forest for new data \(\mathbf{x}^*\) follows by making predictions from the individual trees and aggregating the results by some function \(\sigma\), which is usually the sample mean for regression:

\[ \hat{g}(\mathbf{x}^*) = \sigma(\hat{g}_1(\mathbf{x}^*),...,\hat{g}_B(\mathbf{x}^*)) = \frac{1}{B} \sum^B_{b=1} \hat{g}_b(\mathbf{x}^*) \]

where \(\hat{g}_b(\mathbf{x}^*)\) is the prediction from the \(b\)th tree for some new data \(\mathbf{x}^*\) and \(B\) are the total number of grown trees.

As discussed above, individual decision trees result in predictions with high variance that are not robust to small changes in the underlying data. Random forests decrease this variance by aggregating predictions over a large sample of decorrelated trees, where a high degree of difference between trees is promoted through the use of bootstrapped samples and random candidate feature selection at each split.

Usually many (hundreds or thousands) trees are grown, which makes random forests robust to changes in data and ‘confident’ about individual predictions. Other advantages include having tunable and meaningful hyper-parameters, including: the number of variables to consider for a single tree, the splitting rule, and the stopping rule. Random forests treat trees as weak learners, which are not intended to be individually optimized. Instead, each tree captures a small amount of information about the data, which are combined to form a powerful representation of the dataset.

Whilst random forests are considered a ‘black-box’, in that one cannot be reasonably expected to inspect thousands of individual trees, variable importance can still be aggregated across trees, for example by counting the frequency a variable was selected across trees, calculating the minimal depth at which a variable was used for splitting, or via permutation based feature importance. Hence the model remains more interpretable than many alternative methods. Finally, random forests are less prone to overfitting and this can be relatively easily controlled by using early-stopping methods, for example by continually growing trees until the performance of the model stops improving.

11.2 Random Survival Forests

Unlike other machine learning methods that may require complex changes to underlying algorithms, random forests can be relatively simply adapted to random survival forests by updating the splitting rules and terminal node predictions to those that can handle censoring and can make survival predictions. This chapter is therefore focused on outlining different choices of splitting rules and terminal node predictions, which can then be flexibly combined into different models.

11.2.1 Splitting Rules

Survival trees and RSFs have been studied for the past four decades and whilst there are many possible splitting rules (Bou-Hamad, Larocque, and Ben-Ameur 2011), only two broad classes are commonly utilised (as judged by number of available implementations, e.g., Pölsterl (2020); Wright and Ziegler (2017); H. Ishwaran et al. (2011)). The first class rely on hypothesis tests, and primarily the log-rank test, to maximise dissimilarity between splits, the second class utilises likelihood-based measures. The first is discussed in more detail as this is common in practice and is relatively straightforward to implement and understand, moreover it has been demonstrated to outperform other splitting rules (Bou-Hamad, Larocque, and Ben-Ameur 2011). Likelihood rules are more complex and require assumptions that may not be realistic, these are discussed briefly.

Hypothesis Tests

The log-rank test statistic has been widely utilized as a splitting-rule for survival analysis (Ciampi et al. 1986; B. H. Ishwaran et al. 2008; LeBlanc and Crowley 1993; Segal 1988). The log-rank test compares the survival distributions of two groups under the null-hypothesis that both groups have the same underlying risk of (immediate) events, with the hazard function used to compare underlying risk.

Let \(L^a\) and \(L^b\) be two leaves and let \(h^a,h^b\) be the (theoretical, true) hazard functions in the two leaves respectively and let \(i \in L\) be a shorthand for the indices of the observations in leaf \(L\) so that \(i = 1,\ldots,|L|\). Define:

- \(n_\tau^a\), the number of observations at risk at \(\tau\) in leaf \(a\)

\[ n_\tau^a = \sum_{i \in L^a} \mathbb{I}(t_i \geq \tau) \]

- \(o^a_{\tau}\), the observed number of events in leaf \(a\) at \(\tau\)

\[ o^a_{\tau} = \sum_{i \in L^a} \mathbb{I}(t_i = \tau, \delta_i = 1) \]

- \(n_\tau = n_\tau^a + n_\tau^b\), the number of observations at risk at \(\tau\) in both leaves

- \(o_\tau = o^a_{\tau} + o^b_{\tau}\), the observed number of events at \(\tau\) in both leaves

Recall \(t_{(k)}\) is the \(k\)th ordered event time. Then, the log-rank hypothesis test is given by \(H_0: h^a = h^b\) with test statistic (Segal 1988), \[ LR(L^a) = \frac{\sum_{k=1}^m (o^a_{t_{(k)}} - e^a_{t_{(k)}})}{\sqrt{\sum_{k=1}^m v_{t_{(k)}}^a}} \]

where:

- \(e^a_{\tau}\) is the expected number of events in leaf \(a\) at \(\tau\)

\[ e^a_{\tau} := \frac{n_\tau^a o_\tau}{n_\tau} \]

- \(v^a_\tau\) is the variance of the number of events in leaf \(a\) at \(\tau\)

\[ v^a_{\tau} := e^a_{\tau} \Big(\frac{n_\tau - o_\tau}{n_\tau}\Big)\Big(\frac{n_\tau - n^a_\tau}{n_\tau - 1}\Big) \]

These results follow as under the assumption of equal hazards in both leaves, the number of events at each unique event time is distributed according to a Hypergeometric distribution. The same statistic results if \(L^b\) is instead considered.

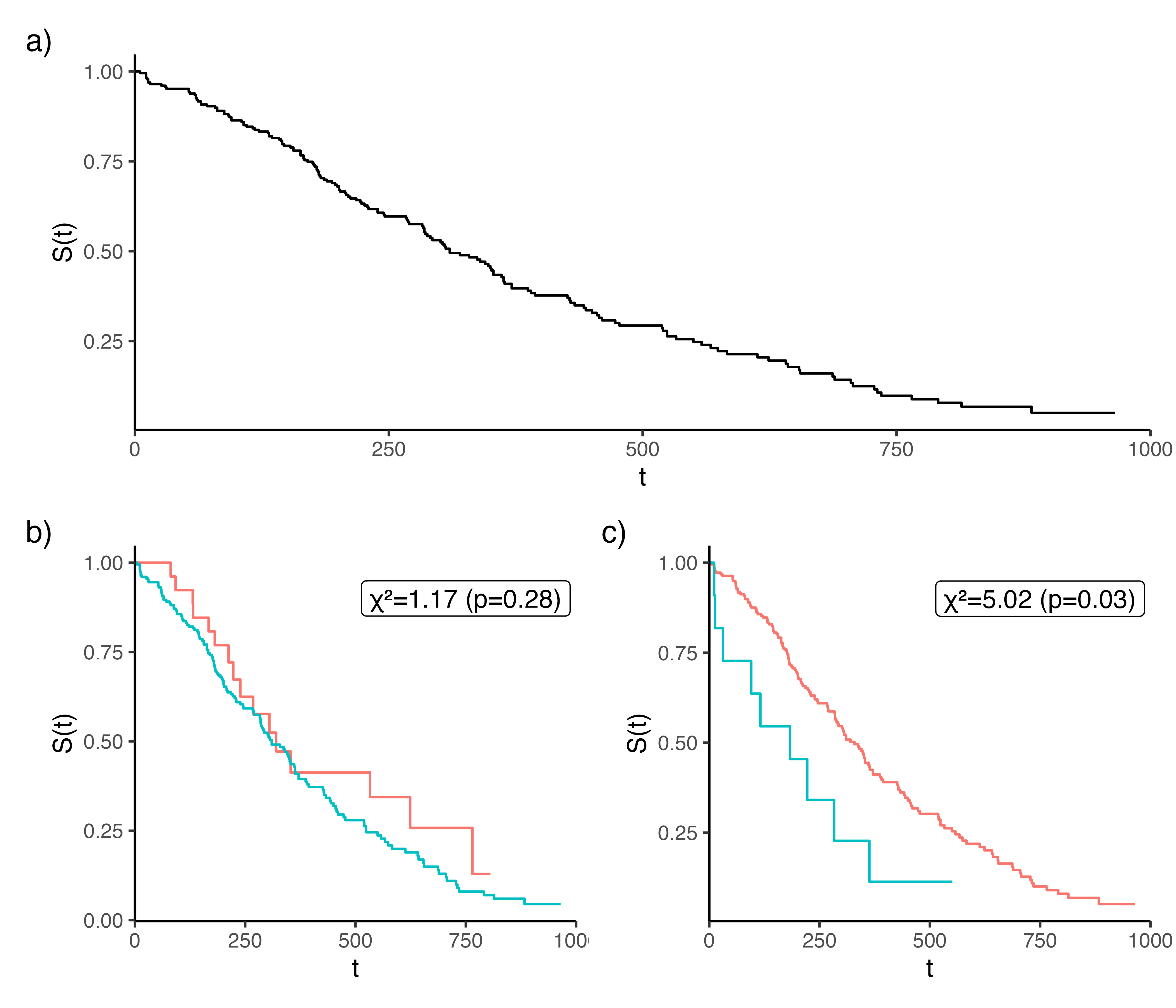

The higher the log-rank statistic, the greater the dissimilarity between the two groups (Figure 11.2), thereby making it a sensible splitting rule for survival, moreover it has been shown that it works well for splitting censored data (LeBlanc and Crowley 1993). Additionally, the log-rank test requires no knowledge about the shape of the survival curves or distribution of the outcomes in either group (Bland and Altman 2004), making it ideal for an automated process that requires no user intervention.

lung dataset from the \(\textsf{R}\) package survival. (b-c) is the same data stratified according to whether ‘age’ is greater or less than 50 (panel b) or 75 (panel c). The higher \(\chi^2\) statistic (panel c) results in a lower \(p\)-value and a greater difference between the stratified Kaplan-Meier curves. Hence splitting age at 75 results in a greater dissimilarity between the resulting branches and thus makes a better choice for splitting the variable.

The log-rank score rule (Hothorn and Lausen 2003) is a standardized version of the log-rank rule that could be considered as a splitting rule, though simulation studies have demonstrated non-significant improvements in predictive performance when comparing the two (B. H. Ishwaran et al. 2008). Alternative dissimiliarity measures and tests have also been suggested as splitting rules, including modified Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Gehan-Wilcoxon tests (Ciampi et al. 1988). Simulation studies have demonstrated that both of these may have higher power and produce ‘better’ results than the log-rank statistic (Fleming et al. 1980), however neither appears to be commonly used.

In a competing risk setting, Gray’s test (Gray 1988) can be used instead of the log-rank test, as it compares cumulative incidence functions rather than all-cause hazards. Similarly to the log-rank test, Gray’s test also compares survival distributions using hypothesis tests to determine if there are significant differences between the groups, thus making it a suitable option to build competing risk RSFs.

Alternative Splitting Rules

A common alternative to the log-rank test is to instead use likelihood ratio, or deviance, statistics. When building RSFs, the likelihood-ratio statistic can be used to test if the model fit is improved or worsened with each split, thus providing a way to partition data. However, as discussed in Section 3.5.1, there are many different likelihoods that can be assumed for survival data, and there is no obvious way to determine if one is more sensible than another. Furthermore the choice of likelihood must fit the underlying model assumptions. For example, one could assume the data fits the proportional hazards assumption and in each split one could calculate the likelihood-ratio using the Cox PH partial likelihood. Alternatively, a parametric form could be assumed and a likelihood proposed by LeBlanc and Crowley (1992) may be calculated to test model fit. While potentially useful, these methods are implemented in very few off-shelf software packages, thus empirical comparisons to other splitting rules are lacking.

Other rules have also been studied including comparison of residuals (Therneau, Grambsch, and Fleming 1990), scoring rules (H. Ishwaran and Kogalur 2018), distance metrics (Gordon and Olshen 1985), and concordance metrics (Schmid, Wright, and Ziegler 2016). Experiments have shown different splitting rules may perform better or worse depending on the underlying data (Schmid, Wright, and Ziegler 2016), hence one could even consider treating the splitting rule as a hyper-parameter for tuning. However, if there is a clear goal in prediction, then the choice of splitting rule can be informed by the prediction type. For example, if the goal is to maximise separation, then a log-rank splitting rule to maximise homogeneity in terminal nodes is a natural starting point. Whereas if the goal is to accurately rank observations, then a concordance splitting rule may be optimal.

11.2.2 Terminal Node Prediction

As in the regression setting, the usual strategy for predictions is to create a simple estimate based on the training data that lands in the terminal nodes. However, as seen throughout this book, the choice of estimator in the survival setting depends on the prediction task of interest, which are now considered in turn. First, note that all terminal node predictions can only yield useful results if there are a sufficient number of uncensored observations in each terminal node. Hence, a common RSF stopping rule is the minimum number of uncensored observations per leaf, meaning a leaf is not split if that would result in too few uncensored observations in the resulting leaves.

Probabilistic Predictions

Starting with the most common survival prediction type, the algorithm requires a simple estimate for the underlying survival distribution in each of the terminal nodes, which can be estimated using the Kaplan-Meier or Nelson-Aalen methods (Hothorn et al. 2004; B. H. Ishwaran et al. 2008; LeBlanc and Crowley 1993; Segal 1988).

Denote \(b\) as a decision tree and \(L^{b(h)}\) as the terminal node \(h\) in tree \(b\). Then the predicted survival function and cumulative hazard for a new observation \(\mathbf{x}^*\) is,

\[ \hat{S}_{b(h)}(\tau|\mathbf{x}^*) = \prod_{k:t_{(k)}\leq \tau} 1-\frac{d_{t_{(k)}}}{n_{t_{(k)}}}, \quad \{k \in L^{b(h)}: \mathbf{x}^* \in L^{b(h)}\} \tag{11.2}\]

\[ \hat{H}_{b(h)}(\tau|\mathbf{x}^*) = \sum_{k:t_{(k)}\leq \tau} \frac{d_{t_{(k)}}}{n_{t_{(k)}}}, \quad \{k \in L^{b(h)}: \mathbf{x}^* \in L^{b(h)}\} \tag{11.3}\]

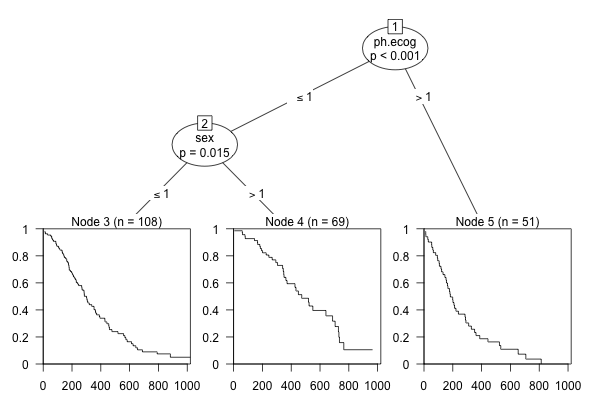

where \(d_{t_{(k)}}\) and \(n_{t_{(k)}}\) are the observed number of events, and the number of observations at risk, respectively at the \(k\)th ordered event time. See Figure 11.3 for an example using the lung dataset (Therneau 2015).

lung dataset from the \(\textsf{R}\) package survival. The terminal node predictions are survival curves.

The bootstrapped prediction is the cumulative hazard function or survival function averaged over individual trees. Note that understanding what these bootstrapped functions represents depends on how they are calculated. By definition, a mixture of \(n\) distributions with cumulative distribution functions \(F_i, i = 1,...,n\) is given by

\[ F(x) = \sum^n_{i=1} w_i F_i(x) \]

Subsituting \(F = 1 - S\) and noting \(\sum w_i = 1\) gives the computation \(S(x) = \sum^n_{i=1} w_i S_i(x)\), allowing the bootstrapped survival function to exactly represent the mixture distribution averaged over all trees:

\[ \hat{S}_{Boot}(\tau|\mathbf{x}^*) = \frac{1}{B} \sum^B_{b=1} w_i\hat{S}_b(\tau|\mathbf{x}^*) \tag{11.4}\]

usually with \(w_i = 1/B\) where \(B\) is the number of trees.

In contrast, if one were to instead substitute \(F = 1 - \exp(-H)\), then the mixture distribution depends on a logarithmic function that can only be approximately computed if predicted survival probabilities are close to one, which is an assumption that deteriorates over time. Therefore, to ensure the bootstrapped prediction accurately represents the underlying mixed probability distribution, the bootstrapped cumulative hazard function should be computed as:

\[ \hat{H}_{Boot}(\tau|\mathbf{x}^*) = - \log (\hat{S}_{Boot}(\tau|\mathbf{x}^*)) \tag{11.5}\]

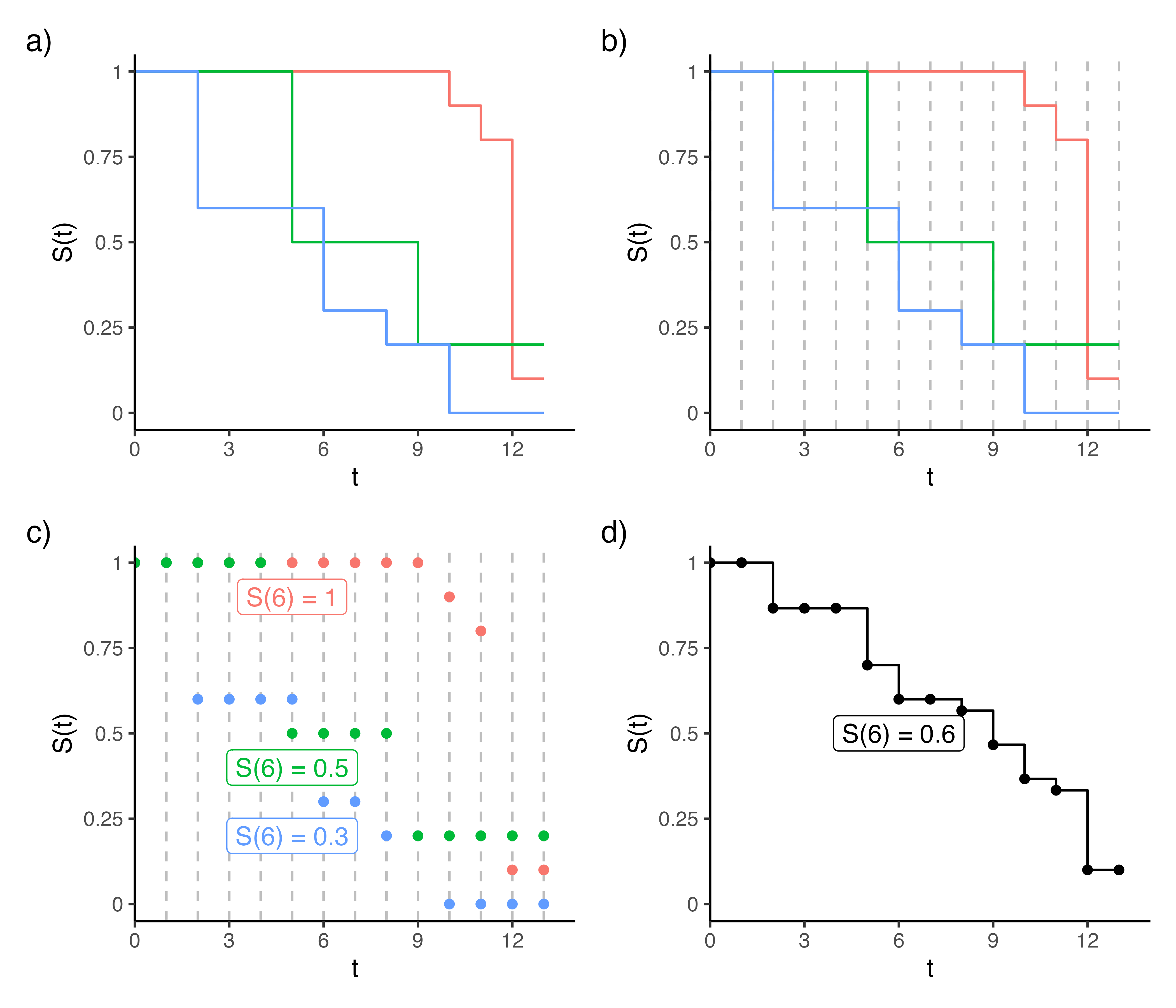

Another practical consideration to take into account is how to average the survival probabilities over the decision trees as each individual Kaplan-Meier estimate may have been trained on different time points. This is overcome by recognising that the Kaplan-Meier estimation results in a piece-wise function that can be linearly interpolated between training data. Figure 11.4 demonstrates this process for three decision trees (panel a), where the survival probability is calculated at all possible time points (panels b-c), and the average is computed with linear interpolation added between time-points (panel d).

Extensions to competing risks follow naturally using bootstrapped cause-specific cumulative incidence functions.

Deterministic Predictions

As discussed in Chapter 9, predicting and evaluating survival times is a complex and fairly under-researched area. For RSFs, there is an inclination to estimate survival times based on the mean or median survival times of observations in terminal nodes, however this would lead to biased estimations. Therefore, research has tended to focus on relative risk predictions.

As discussed, relative risks are arbitrary values where only the resulting rank matters when comparing observations. In RSFs, each terminal node should be as homogeneous as possible, hence within a terminal node, the risk between observations should be the same. The most common method to estimate average risk appears to be a transformation from the Nelson-Aalen method (B. H. Ishwaran et al. 2008), which exploits results from counting process to provide a measure of expected mortality (Hosmer Jr, Lemeshow, and May 2011) – the same result is used in the van Houwelingen calibration measure discussed in Section 7.1.2. Given new data, \(\mathbf{x}^*\), falling into terminal node \(b(h)\), the relative risk prediction is the sum of the predicted cumulative hazard, \(\hat{H}_{b(h)}\), computed at each observation’s observed outcome time:

\[ \phi_{b(h)}(\mathbf{x}^*) = \sum_{i=1}^m \hat{H}_{b(h)}(t_i|\mathbf{x}^*) \]

where \(\hat{H}_{b(h)}\) is the terminal node prediction as in 11.3. This is interpreted as the number of expected events in \(b(h)\) and the assumption is that a terminal node with more expected events is a higher risk group than a node with less expected events. The bootstrapped risk prediction is the sample mean over all trees:

\[ \phi_{Boot}(\mathbf{x}^*) = \frac{1}{B} \sum^B_{b=1} \phi_{b(h)}(\mathbf{x}^*) \]

More complex methods have also been proposed that are based on the likelihood-based splitting rule and assume a PH model form (H. Ishwaran et al. 2004; LeBlanc and Crowley 1992). However, these do not appear to be in wide-spread usage.